The Phoenicians and the First Can of Tuna

________________

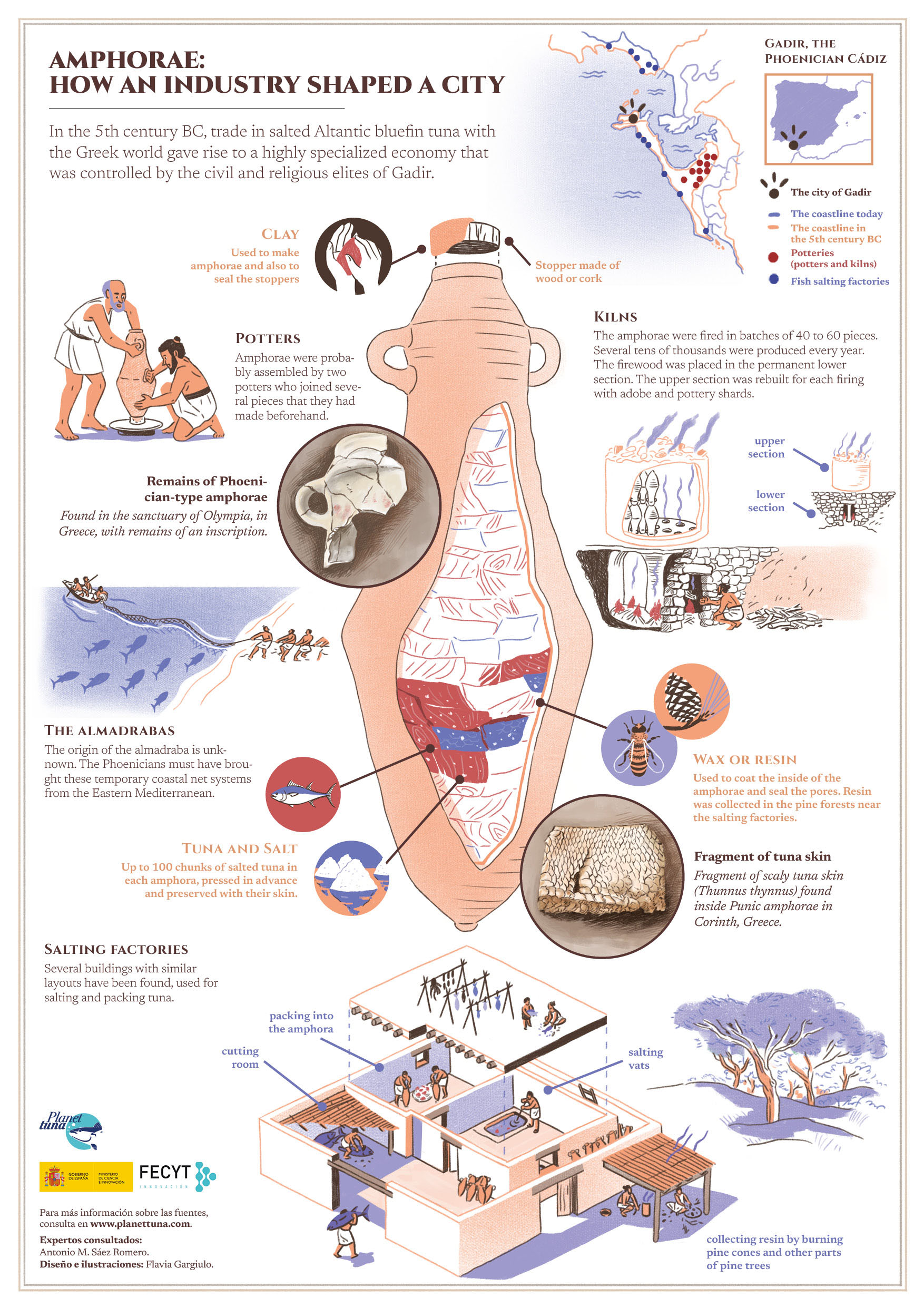

The salted tuna produced along the Strait of Gibraltar during Phoenician times, in the sixth century BC had to travel a long way to please the Greek palate. It was essential that it be processed and stored in a way that preserved its quality and made it easy to ship. Phoenician amphorae are the forerunners of today’s cans of tuna: they were used to carry the fish from the Strait of Gibraltar to Classical Greece. And not only that – the remains of amphorae found in both of these places have been key for reconstructing the history of Atlantic bluefin tuna fishing and preserving, which was so important and has had such a powerful social, cultural, and economic impact in Andalusia up until today.

Although amphorae were the cutting-edge technology of their times, there is still a lot we don’t know about their complex production. Designed to be sturdy and airtight, they were coated on the inside with a thin layer of beeswax and pine resin to seal the pores in the ceramic surface. We have no information about how the openings of these vessels were closed; wood or cork stoppers may have been used, attached to the mouth of the amphorae with clay. Given how slow and unsafe travel by land was at the time, the sea was the highway on which they traveled in the spring and summer, when the tunas entered the Mediterranean and the sea was at its calmest. Given the lack of archeological data on Phoenician shipwrecks, we have to imagine dozens of amphorae tied to each other in the holds of ships, with their pointed bases stuck in sand or another material used as ballast, firmly set and secured to prevent the cargo from shifting and the ship from capsizing.

From the Harbor Straight to the Table

The Phoenicians preserved tuna by salting it. Roughly a hundred salted cubes or fillets were placed – possibly after being pressed – in amphorae measuring up to one meter in length and weighing over fifty kilos. Once they arrived in Greece, the salted fish was eaten in taverns along with the finest wines of that period, which would explain the large number of traces of wine found in amphorae and cups next to remains of tuna. Greek authors such as Athenaeus of Naucratis joke about the thirst for wine when one ate this salty fish snack. Today, salt curing is a widespread food processing method. It was also used by the Greeks and the Phoenicians, but they often desalted fish and cooked it in oil, wine, and herbs before eating it.

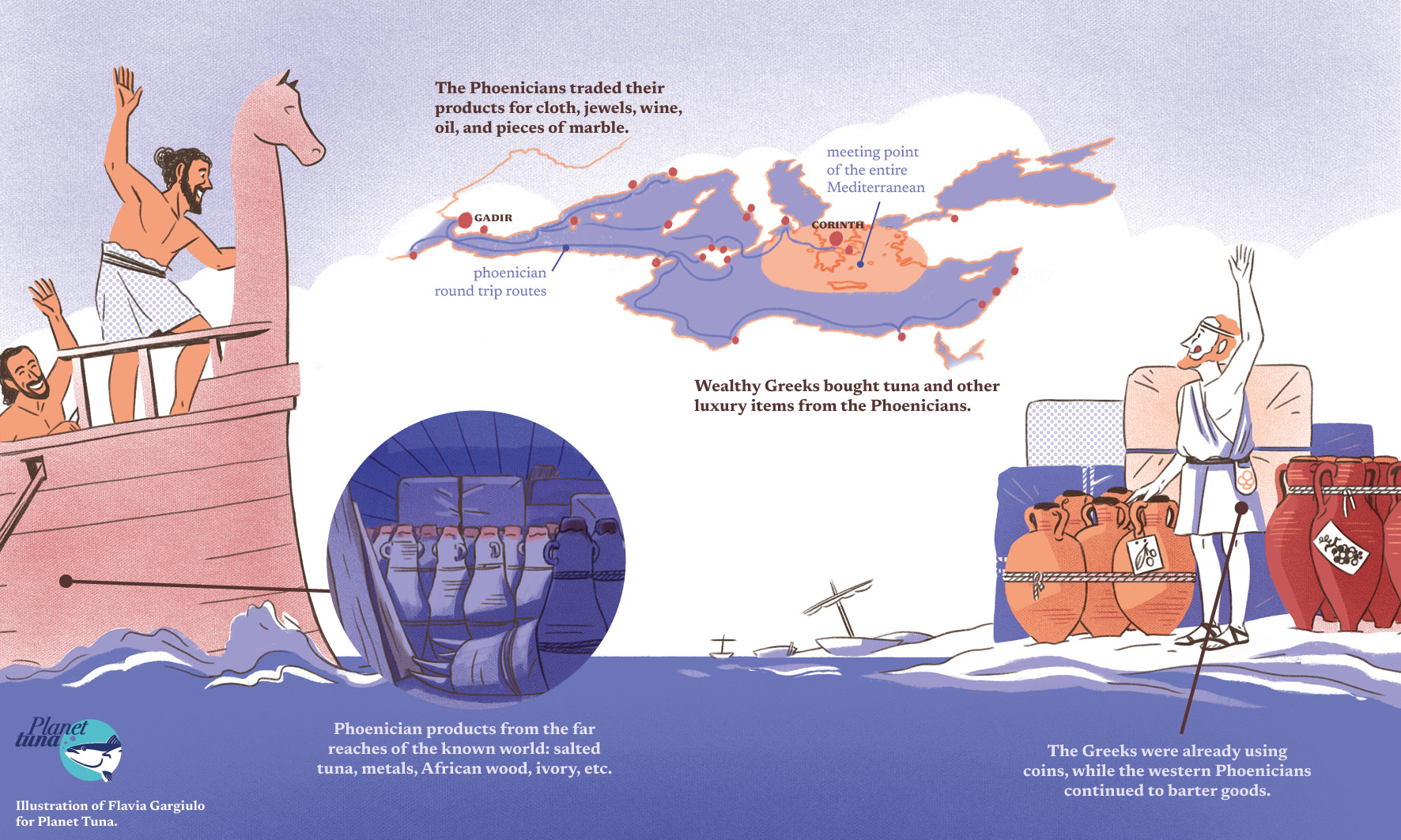

To find out about the tuna trade and its pricing, we have to rely on written Greek sources. Almost all the records of Phoenician culture have been lost, because they were written on less durable materials such as parchment or clay tablets. Strangely enough, we don’t even know for sure how tuna was written in Phoenician! What we do know is that it was much cheaper in the West – where it was produced locally – than in the East, where it was essentially an imported, exotic item – available in limited supply, expensive, and in high demand. Apparently the Greeks didn’t pay the Phoenicians with money, although coins had already been developed in the Eastern Mediterranean in the sixth or seventh century BC. Most likely the Phoenicians were paid in kind for their tuna with goods which they would then sell for a profit in the West, given the appeal of their coming from faraway lands (luxury fabrics, glass objects, wines, etc.)

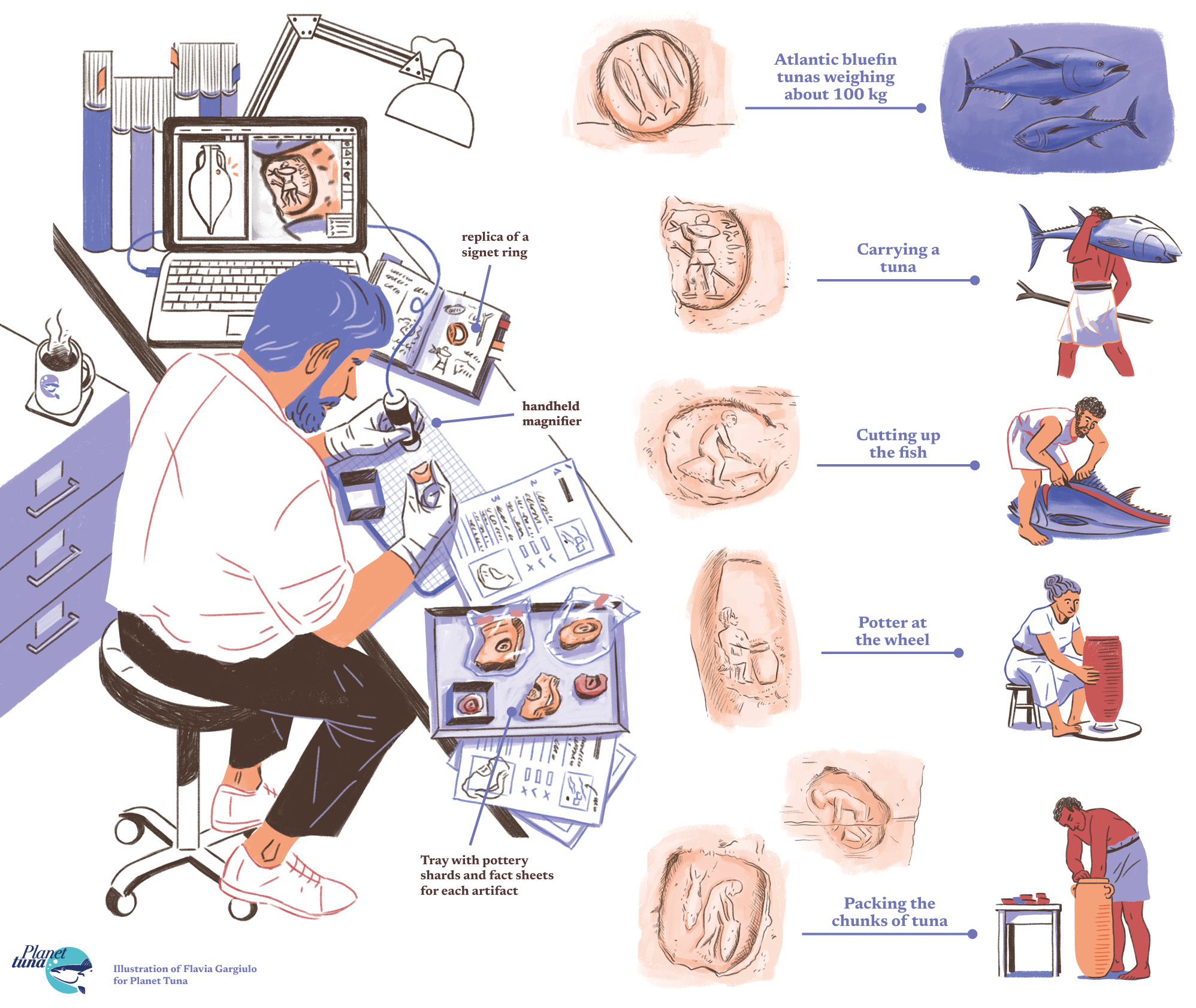

From the 4th-3rd centuries BC onward, some amphorae were sealed with signet rings representing the different trades in the salting industry, among other subjects.

To know the expiration date of Phoenician tuna, we have to use our imagination: we don’t really know how long the contents of an amphora may have lasted. We can assume it would have kept for years, as long as the amphora remained airtight, but we don’t yet have enough evidence to estimate a “use-by date.” In any case, it doesn’t seem likely that either the Greeks or the Phoenicians would wait long enough to let this delicacy go to waste.

Only the Beginning: There Is Still Much to Be Discovered

According to Manuel Sáez Romero, a researcher and professor at the Universidad de Sevilla, there’s still a lot we don’t know about the age-old history of tuna and its relationship with the Phoenicians. Research continues, in archeological sites and laboratories, both in the places where the fish was preserved and those where it was sold and eaten. From Cádiz to Greece, several projects are providing new data about the vats where the pieces of tuna were salted and the taverns where the fish was cooked in simple ways and served with the finest Greek wines. Researchers are also analyzing the seals stamped on the amphorae as tracking marks, which contain scenes that succinctly describe tuna fishing, shipping, and packing.

Tuna from the Strait of Gibraltar, a key product in commercial exchanges between Greeks and Phoenicians in the 5th century BC.

This fascinating history tells us about a time when Mediterranean cultures not only began to value (and pay high prices for) tuna, but also started to eat and celebrate in similar ways, laying the groundwork for our current Mediterranean diet and our basic cooking practices.

This content is part of the ocean education program, Centinelas, and deals on Sustainable Development Goal 4, Quality Education.

In collaboration with: