From the Strait of Gibraltar to Greece. The Tuna Trade in Phoenician Times

________________

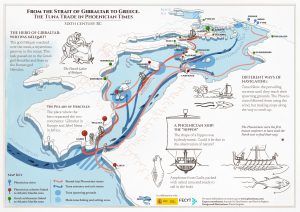

Fifth century BC, about 2,500 years ago. A Phoenician ship is sailing from the area that is now Cádiz to the Greek city of Corinth carrying a shipment of preserved tuna. Although it may seem like a trivial anecdote, what we’re witnessing is the birth of an industry that moves millions of euros today: canned tuna.

Thanks to the archeological remains and the research carried out in the Strait of Gibraltar and in Greece, we know that Phoenician salted tuna was very popular in Classical Greece, and the Phoenicians were the ones who began the first “globalization” of a seafood product in the Mediterranean, much earlier than the Romans did. And now, we’re going to tell you its story.

The tradition of preserving fish goes even further back. To find out about it, we have to travel to Mesopotamia and Egypt, by the banks of the great rivers – the Tigris, the Euphrates, and the Nile – where this groundbreaking method was born, making it possible to keep perishable foods such as fish. The origin of preserved tuna is actually unclear; apparently, it may have first appeared in the Near East or in ancient Greece. However, the Phoenicians were the first to develop a powerful economic activity based on fishing, preserving, and trading with this fish. Tuna went from being eaten locally in several areas of the Mediterranean to becoming a delicacy that traveled thousands of kilometers, from the Strait of Gibraltar all the way to Greece.

Tunas and Phoenicians: The Kings of the Mediterranean

Who were the Phoenicians? And how did these people from the Eastern Mediterranean end up settling along the coast of Cádiz? We wish we knew more about them; they vied with Greece and opened up trade routes across the entire Mediterranean Sea. The Phoenicians left us little in the way of written documents, as they were a primarily commercial culture and used perishable materials for their notes and accounts. To learn more about them, we have to resort to archeology and to Greek sources, written by their main competitors and also their commercial allies.

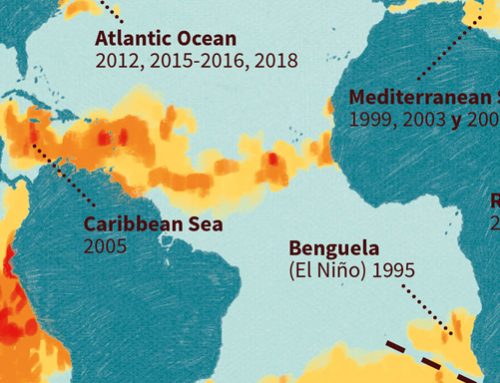

Some researchers claim that the Phoenicians spread across the Mediterranean in search of tuna, and if we cross-reference the maps of the main areas of Phoenician dominance with the migration routes of Atlantic bluefin tuna, we see that the overlap is astonishing. Both the tunas and the Phoenicians were great seafarers; they shared an extraordinary ability to orient themselves and to travel great distances in the sea. Tunas are anatomically designed to cover thousands of kilometers; the Phoenicians, in turn, expanded across the Mediterranean thanks to their innovations in shipbuilding. For centuries, they were the lords of the Mediterranean Sea, following the same routes as the tunas and covering the round trip from West to East in roughly the same time.

From Local Food Source to “Global” Product

Much as today, the large schools of mature bluefin tuna coming from the Atlantic Ocean crossed the Pillars of Melqart (or Hercules, for the Greeks), as the Strait of Gibraltar was known at the time. That was where the Phoenicians caught the fish. Locally-sourced tuna – if that’s what we can call it, given that the species traveled over 5,000 kilometers before being caught – was eaten fresh. Archeological remains in southern Spain suggest that it was an affordable food, easy to come by in any household in the harbor towns where the Phoenicians had settled.

The development of the tuna processing industry in the late sixth century BC coincides with the growing popularity of tuna among the Greeks. Although its origin may very well date back further, it was from this moment on that it became an expanding business and one of the main economic activities in the area around the Strait of Gibraltar, growing from local, small-scale consumption to a massive trade that reached far from its source of production. The species was also present in the East, but it was not fished in such large volumes given its scarcity in comparison with the Strait of Gibraltar and the development of a powerful production industry that was unparalleled in other areas of the Mediterranean. The use of almadraba traps along the coast of Cádiz led to a considerable increase in catches and the industrial processing of Atlantic bluefin tuna to supply an expanding delicacy market.

Tuna shipping and conservation was related to key sectors of the economy during that period: salt production, ceramics, beekeeping, resin extraction, shipbuilding, almadraba fishing, and many more. Fishing and salting were driving forces for many other activities, and all together they employed a large part of the population, allowing the promoters of the business to amass large fortunes.

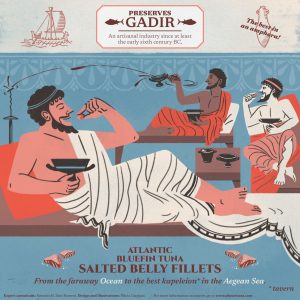

From the sixth century BC onwards, the local market in western Andalusia declined as exports increased towards the east, primarily to Greece, where tuna was considered a delicacy due to its quality and exotic appeal, yielding higher profits. Archeological remains have revealed tuna preserves in shrines, markets, and the homes of the Greek upper class, as well as in the equivalent of early taverns. In fact, the comedies staged during those times included satirical mentions of opsofagi (fish-eaters), referring to the wealthy class and the unethical wastefulness of eating this gourmet product. The new fashion was there to stay.

The relationship between humans and tunas goes back a long way. Today it strikes us as surprising that the Japanese fishing industry has joined the tuna supply chain along the coast of Cádiz, raising prices and shipping the fish thousands of miles to be eaten as a luxury product. However, if we look back, we realize they are not the first to do so – the Phoenicians turned tuna into a “global” product as early as the sixth century BC.

More references to read

-Sáez Romero, A.M., Belizón, R., Fantuzzi, L. (2020): “Almadrabas trimilenarias. En busca de los atunes del Estrecho en la Grecia Clásica“, Andalucía en la Historia 69, pp. 56-60. https://www.

-Sáez Romero, A.M., Theodoropoulou, T., Belizón, R. (2020): “Atunes púnicos y vinos egeos en una taberna de la Grecia Clásica. Resultados iniciales del Corinth Punic Amphora Building Project“, en S. Celestino – E. Rodríguez (eds.) Un viaje entre el Oriente y el Occidente del Mediterráneo / A Journey between East and West in the Mediterranean. Mytra 5, vol. II, IAM-CSIC, Mérida, pp. 817-835.

-Fantuzzi, L., Kiriatzi, E., Sáez Romero, A.M., Noémi S. Müller, Williams II, C.H. (2020) “Punic amphorae found at Corinth: provenance analysis and implications for the study of long-distance salt fish trade in the Classical period.” Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences 12, 179.

-Sáez Romero, A.M., y García Vargas, E. (2019): “La producción y comercio de ánforas y conservas de pescado en la Bahía de Cádiz en época fenicio-púnica. Nuevos datos, métodos y enfoques para viejos debates“, en Álvarez Melero, A., Álvarez-Ossorio Rivas, A., Bernard, G., Torres González, V. A. (Coords.): Fretum Hispanicum. Nuevas perspectivas sobre el Estrecho de Gibraltar durante la Antigüedad. Editorial de la Universidad de Sevilla, pp.

-Sáez Romero, A.M. y Muñoz Vicente, A. (2016): “Los orígenes de las conservas piscícolas en el Estrecho de Gibraltar en epoca fenicio-punica“, en D. Bernal, J. Expósito, L. Medina y J.B. Vicente-Franqueira (eds.) Un Estrecho de conservas. Del garum de Baelo Claudia a la melva de Tarifa. Editorial UCA, Cádiz, pp. 23-41.

-Sáez Romero, A. M. 2014b: “Fish processing and salted-fish trade in the Punic West: new archaeological data and historical evolution“, E. Botte y V. Leitch (eds.) Fish & Ships: Production et commerce des salsamenta durant l’Antiquité(Actes de l’atelier doctoral, Rome 18-22 juin 2012), Bibliothèque d’Archéologie Méditerranéenne et Africaine 17, Aix-en-Provence, 159-174.

-Sáez Romero, A. M. 2011: “Balance y novedades sobre la pesca y la industria conservera en las ciudades fenicias del “área del Estrecho”“, D. Bernal Casasola (ed.), Pescar con Arte. Fenicios y romanos en el origen de los aparejos andaluces. Monografías del Proyecto Sagena, 3. Almería, 255-297.

-Muhling, B.A., Lamkin, J.T., Alemany, F. et al. Reproduction and larval biology in tunas, and the importance of restricted area spawning grounds. Rev Fish Biol Fisheries 27, 697–732 (2017).

-Cermeño P, Quílez-Badia G, Ospina-Alvarez A, Sainz-Trápaga S, Boustany AM, Seitz AC, et al. (2015) Electronic Tagging of Atlantic Bluefin Tuna (Thunnus thynnus, L.) Reveals Habitat Use and Behaviors in the Mediterranean Sea. PLoS ONE 10(2): e0116638.

-Reglero P, Balbín R, Abascal FJ, Medina A, Alvarez-Berastegui D, Rasmuson L, Mourre B, Saber S, Ortega A, Blanco E, de la Gándara F, Alemany FJ, Ingram GW, Hidalgo M (2019) Pelagic habitat and offspring survival in the eastern stock of Atlantic bluefin tuna. ICES Journal of Marine Science, fsy135.

-Aranda G, Abascal FJ, Varela JL, Medina A (2013) Spawning Behaviour and Post-Spawning Migration Patterns of Atlantic Bluefin Tuna (Thunnus thynnus) Ascertained from Satellite Archival Tags. PLoS ONE 8(10): e76445.

This content is part of the ocean education program, Centinelas, and deals on Sustainable Development Goal 4, Quality Education.

In collaboration with: