Canned tuna III. What is faux fish and why does it matter? Food security and tropical tuna fishing in Africa

________________

In this article, we will find out about faux poisson, its importance as a source of protein for many people in Africa, its relationship to the international seine fishing that operates in the Atlantic and Indian Ocean waters off Africa, its social, environmental and economic impact, and the need for intervention by fishing management organizations. Let’s start by identifying why we should care about this product.

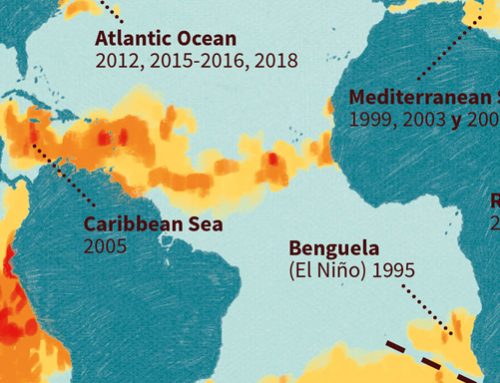

Faux poisson is fish that is caught by purse seiners fishing for tropical tuna (primarily skipjack tuna and also yellowfin and bigeye tuna) in African coastal waters for the production of canned tuna, and discarded either because it does not satisfy the requirements established by the canning industry or because it does not belong to the target species of tropical tuna. This by-catch is sold in local African markets. It is estimated that about 16% of the catch from international seine fishing of Atlantic tuna ends up feeding millions of people on the coast of west Africa. This accidental catch, known as faux poisson, is one of the main sources of protein in countries such as Côte d’Ivoire, Senegal and Ghana.

A large number of purse seiners dedicated to tuna fishing operate in the coastal waters of west and east Africa. Although seine fishing is more selective than other methods, the introduction of fish-aggregating devices (FADs) has increased the catch of non-target species and of target individuals that do not meet commercial standards due to their size or condition. Among these non-target species are sharks, small tuna (E. alletteratus, A. thazard, A. rochei) and marlin and other bony fish.

Such catches have grown in importance, both in terms of volume and due to their commercial value in African markets. The fishing vessels are obliged to land all of their catch in port, with certain exceptions, and the tropical tuna is then sold on the international market for the production of canned tuna. The rest is sold in local markets as fresh or smoked product for human consumption.

The case of Côte d’Ivoire

In west Africa, faux poisson is primarily landed in Côte d’Ivoire, Senegal and Ghana. The capital of Côte d’Ivoire, Abidjan, is one of the main ports. Some of the faux fish that is landed here comes from international purse seiners from Spain, France and Ghana, while the rest is landed in other nearby countries and then imported. The consumption of faux fish is very popular in the city, and is of great economic and social importance to the local population. Some of the fish that is landed is then transported to other cities within Côte d’Ivoire or to other countries, such as Burkina Faso and Mali. The tuna that stays in Abidjan is prepared as garba, a dish of fried fish and semolina served at busy street stalls known as garbadromes. Another issue is the lack of sanitary controls on faux fish. The fish is frozen on board the purse seiners, but after it has been landed the conditions of storage and refrigeration are inadequate.

Food security and protecting biodiversity

When assessing this ecological and fishing resource, it is difficult to disentangle food, environmental and social issues. Food is a global challenge, and it plays a particularly vital role in Africa, where the population is forecast to multiply by four by 2100. Although Africa still consumes less fish than other continents, fish is the main source of animal protein and the demand for faux poisson in Côte d’Ivoire is very high, as the country only catches a third of the fish it consumes, with the rest coming from international seine fishing or from other countries. Any policies to regulate discards must take this demand into account. Although by-catch is now more closely monitored than it once ways, and international law protects sharks, rays and other species, further improvements are required to ensure more reliable information about the impact on marine diversity so that measures can be taken to improve management.

Text by Anna Aguiló

Experts consulted:

Francisco Abascal, Pedro Pascual, Vanessa Rojo and Lourdes Ramos from IEO Canarias, Justin Monin Amande from African Marine Expertise, Miguel Ángel Herrera from OPAGAC and Laura Leyva from IEO.

This content is part of the ocean education program, Centinelas, and deals on Sustainable Development Goals 12, Responsible Consumption and Production, 14, Life Under Water, 10, Reduced Inequalities, and 2, Zero Hunger.

With the collaboration: