Canned Tuna (II). The Journey of a Can

________________

Canned tuna is popular around the world. If you peek inside the kitchen cabinets in any household, you’re likely to find a can waiting to be opened. Canned tuna as we know it today was first manufactured in the late nineteenth century and developed at a spectacular rate over the course of the twentieth century. Spain is the main producer of canned tuna in Europe (64%), ranking second worldwide, after Thailand. The Spanish canning industry is diverse, including 640 companies of all sorts, with small and mid-sized firms working alongside major food corporations.

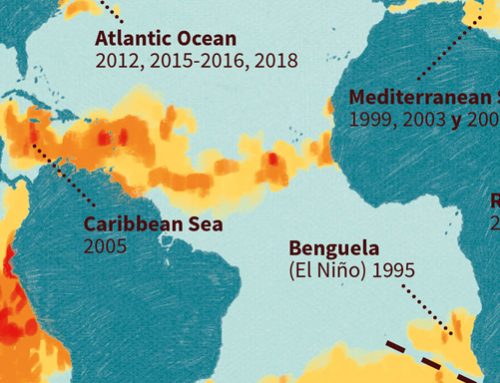

The food system is increasingly delocalized and globalized, and canned tuna is no exception. Each one of the steps in this process has an environmental impact that includes the carbon footprint for the entire production, processing, and marketing chain, as well as the direct consequences of fishing on species and habitats. Understanding the complexities of the journey of a can of tuna is a complicated task because of the many intermediate steps that come into play and the lack of access to information about the products traceability, among other factors.

Where It All Begins

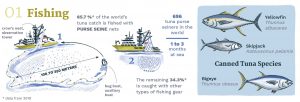

The international purse seine fishing industry for tropical tuna is huge. There are a total of 696 registered large purse seiners, 27 of which fly a Spanish flag. These ships catch the fish in large purse seine nets that surround the schools of tuna. Currently, this method is made easier by fish-aggregating devices (FADs), which are floating objects under which schools of tuna of various species gather.

Large purse seiners can spend from one to three months fishing at sea. These ships are equipped with large-capacity freezers where the tuna can be stored as they are caught. When their holds are full, they sail back to port. The Spanish fleet operates primarily in the Atlantic and Indian Oceans, and its main landing ports are the Seychelles in the Indian Ocean; the Ivory Coast, Senegal, and Cape Verde in the Atlantic; and Ecuador in the Pacific. But those are not the only ones: in recent years, major ports in Madagascar and American Samoa, among others, have been added to the list. Besides, purse seine fishing is not the only method used for catching tuna: yellowfin and bigeye are also caught by industrial longline and bait boat fisheries, in addition to artisanal fisheries in all the oceans.

From the Port to the Consumer

The first sale from the fishermen to the canneries takes place right in the landing port. Once they close their deal, the tuna is processed by canning companies located in the same towns as the ports, or shipped in huge refrigerated cargo ships to canneries in other countries.

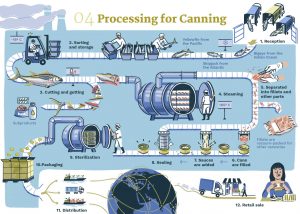

Tuna processing includes six main stages:

- Receiving the frozen tuna in the plants where it is sorted and stored in refrigerators.

- After thawing, the tunas are cut up and gutted by hand.

- The fish is steamed.

- It is left to cool and the fillets are separated from other parts.

- The cans are filled with the fish and a variety of sauces and marinades. They are then sealed and sterilized.

- The cans are packaged for distribution and sale.

The Environmental Impact of Tuna Canning

Aside from the impact that tuna fishing may have on the species that are caught and the carbon footprint resulting from the entire process, there are other effects to be taken into account as tuna makes it way to our table:

-Non-target catches: although purse seine fishing is more selective than other methods, the introduction of fish-aggregating devices (FADs) has increased catches of non-target species such as small tunas and sharks, as well as juveniles of the target species. Particularly in Africa, these associated catches that are not used by the canneries are referred to as faux poisson and supply local markets in many African countries, providing an important source of protein.

-Ghost fishing: by-catch caused by derelict fishing gear that drifts and continues to catch all sorts of species.

-Marine litter: caused by derelict fishing gear.

Aside from the direct impact of fishing, there are also other problems related to tuna processing for its consumption as canned products. The canning industry can generate 50 to 70% of solid waste (heads, bones, guts, gills, dark muscles, and skin) that are not used for canning, as well as other waste resulting from cooking the product. The extent to which these byproducts

are used to produce fishmeal and oil varies widely, and is important to know in order to

determine the overall impact of fishing tuna.

The Purpose of Certifications

When we talk about a sustainable product, there are many factors we have to take into account, and they affect each and every one of its stages. To do so, we have to consider both the environmental impacts and other socio-economic aspects involved in the production and marketing process. The lack of transparency and traceability of canned products makes it difficult for us to make responsible decisions about what we consume. Nowadays, there are different certifications or seals for canned food brands. The Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) certification is the most widespread among them for assessing the sustainability of products from industrial fisheries. However, there are still many areas of the tuna fishing and canning industry where further research is needed so that we can measure its carbon footprint and improve traceability, labelling and consumer information, which is currently inadequate.

Sources:

Fonteneau, A., Chassot, E. and Gaertner, D. (2015). Managing tropical tuna purse seine fisheries through limiting the number of drifting fish aggregating devices in the Atlantic: food for thought. ICCAT Collective Volume of Scientific Papers,71(1), 460- 475

Gamarro, E. G., Orawattanamateekul, W., Sentina, J., and Gopal, T. S. (2013). Byproducts of tuna processing. GLOBEFISH Research Programme, 112, I.

García Del Hoyo, J. J., Jiménez Toribio, R., and García Ordaz, F. (2019). Análisis de las interrelaciones entre la evolución de la flota atunera española y el sector conservero

Hospido, A., Vazquez, M. E., Cuevas, A., Feijoo, G., and Moreira, M. T. (2006). Environmental assessment of canned tuna manufacture with a life-cycle perspective. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 47(1), 56-72

ISSF. 2021. Status of the world fisheries for tuna. Sept. 2021. ISSF Technical Report 2021-13. International Seafood Sustainability Foundation, Washington, D.C., USA

Justel-Rubio, A. and Recio, L. (2021). A Snapshot of the Large-Scale Tropical Tuna Purse Seine Fishing Fleets as of July 2021 (Version 9). ISSF Technical Report 2021-12. International Seafood Sustainability Foundation, Washington, D.C., USA

P.A.H. Medley. J. Gascoigne and G. Scarcella. 2022. An Evaluation of the Sustainability of Global Tuna Stocks Relative to Marine Stewardship Council Criteria (Version 9). ISSF Technical Report 2022-03. International Seafood Sustainability Foundation, Washington, D.C., USA

van Putten, I., Longo, C., Arton, A., Watson, M., Anderson, C. M., Himes-Cornell, A., Obregon, C., Robinson, L and van Steveninck, T. (2020). Shifting focus: The impacts of sustainable seafood certification. PloS one, 15(5), e0233237

Webb, E. L. (2003). Process control parameters for Skipjack tuna (Katsuwonus pelamis) precooking (PhD). NC State University

This content is part of the ocean education program, Centinelas, and deals on Sustainable Development Goals 12, Responsible Consumption and Production, 14, Life Under Water, 10, Reduced Inequalities, and 2, Zero Hunger.

With the collaboration: