Canned Tuna (I) What’s in the Can?

________________

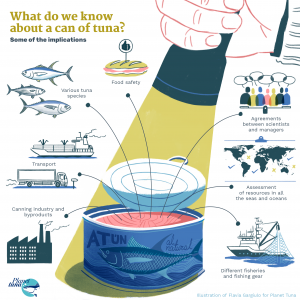

What’s inside a can of tuna? Where was the tuna fished? How was it caught? How was the can distributed and processed? How can we know what we’re eating? When you go to a store or a supermarket and drop a can of tuna into your shopping cart, you’re not likely to be aware of its whole backstory. We’re offering you a set of articles and videos to tell you everything we know (and we wish we knew more) so that the next time you choose a can of tuna from the shelves, you know a bit more about the long journey it travelled before you decided to buy it and eat it.

The global food system is complex. The sourcing, processing, distribution, and sale of food have considerable economic social and environmental implications. The whole network is sometimes so hard to follow and the available information so lacking in transparency that, as consumers, we lose track of what we’re eating and how it made its way to our table. In the case of a can of tuna, information about the species, its conservation status, and where it was caught tends to be very limited. What we do know is that, most likely, when you open a can you’re about to eat tuna of various different species, and sometimes, given the global scale of the industry, the fish was caught in different fishing areas (FAO areas). As you can see, this is a story with some clear facts and many questions still to be answered.

Tropical Tunas and Their Importance within the Food System (and in a Can of Tuna)

Tunas are a large fish family that includes well-known species such as Atlantic bluefin or albacore, but not all of them end up in the can you’ll be opening today to spread on your sandwich or toss into your salad. In the tuna family there’s a group known as the tropical tunas, because they are fished in the tropical and subtropical areas of the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic Oceans. More specifically, there are three species that are most often found in cans: skipjack (Katsuwonus pelamis), yellowfin, also known as ahi (Thunnus albacares), and bigeye (Thunnus obesus). To give you a sense of their importance in terms of trade, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) in the past ten years skipjack has been the third most fished species in the world and is mostly marketed in cans. Next in line after skipjack, we find yellowfin and bigeye tuna, which are also sold fresh and frozen.

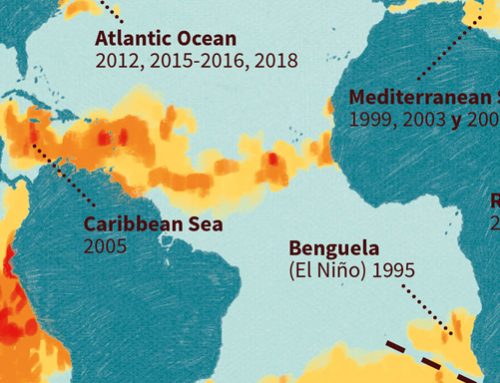

These three species are all very gregarious, very fertile, and highly migratory, and they are broadly distributed across the world’s oceans. These particularities make them abundant prey and highly attractive for the canning industry, which needs access to large amounts of raw material. In addition to the direct impact of the fishing industry, these species are also affected by global warming: in recent years we have been seeing tropical tuna populations move into new areas and extend their distribution range, as is the case of skipjack, which has appeared in the Mediterranean.

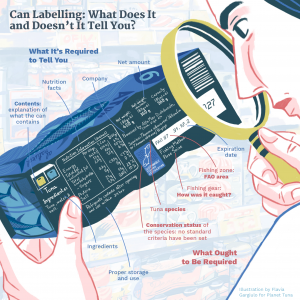

Can Labelling

Now comes the moment of truth: you’re standing in front of a shelf full of cans of tuna. Ideally, what information should you have, and what do you actually find? You should at least be able to find out what species the can contains, the place where it was fished, and its conservation status. Unlike fresh tuna labelling, the regulations are much looser for canned tuna. According to the European Directive, nutrition information and a “best before” date are mandatory, whereas the species, catch area, or fishing gear data are not required for canned fish. This makes it very difficult to make a well-informed, responsible purchase. However, some canning companies and distributors are providing more information than is legally required, such as the species or the catch area (identified with the FAO area number, which divides ocean masses into sections for the classification and control of fishing areas). Some even offer traceability systems on their websites, but in many cases we can only check this information after we open the cardboard packaging around the cans, since the details are on the inside.

What is the Conservation Status of Tropical Tuna Species?

There are specific organizations known as Regional Fisheries Management Organizations (RFMOs) that manage access to living marine resources, including tropical tunas, in the international waters and exclusive economic zones of many countries. Specifically, there are four RFMOs that manage tropical tuna populations and fisheries: ICCAT (Atlantic), IOTC (Indian Ocean), WCPFC (Western and Central Pacific) and IATTC (Eastern Pacific). These organizations, among others, evaluate the status of the stocks and fisheries in their areas of responsibility and develop management measures aimed at ensuring that they stay at optimal levels to guarantee their long-term sustainability.

As you might expect, tropical tuna species attract a great deal of interest from different countries and fisheries because of their value as economic assets and consumer goods. Currently, the scientific committees from various tuna RFMOs consider that the different skipjack populations are not being overfished. For bigeye and yellowfin tuna, on the other hand, there are areas that have surpassed the maximum sustainable yield –for example, bigeye tuna in the Atlantic or yellowfin in the Indian Ocean, spurring the implementation of measures aimed at recovering the population status.

Despite the efforts to manage species and monitor their conservation, at this point, the information we have access to is not nearly enough. There is still much to be done before we consumers have the data that allow us to make responsible decisions: species, sources, fishing methods, and conservation status. This information has to improve until all stakeholders –scientists, the industry, and fisheries management– are able to join forces and calculate the carbon footprint, which is an indication of a product’s environmental impact.

Related content about the tuna can in Planet Tuna:

Canned Tuna (II). The Journey of a Can

The Journey of a Tuna Can Infographics

The Journey of a Tuna Can Video

Sources:

FAO. 2020. El estado mundial de la pesca y la acuicultura 2020. La sostenibilidad en acción. Roma.

ISSF. 2021. Status of the world fisheries for tuna. Mar. 2021. ISSF Technical Report 2021-10. International Seafood Sustainability Foundation, Washington, D.C., USA.

Gephart, J. A., and Pace, M. L. (2015). Structure and evolution of the global seafood trade network. Environmental Research Letters, 10(12), 125014.

MSC. 2020. Marine Stewardship Council. Guía sostenible del atún.

Crippa, M., Solazzo, E., Guizzardi, D., Monforti-Ferrario, F., Tubiello, F. N., and Leip, A. J. N. F. (2021). Food systems are responsible for a third of global anthropogenic GHG emissions. Nature Food, 2(3), 198-209.

This content is part of the ocean education program, Centinelas, and deals on Sustainable Development Goals 12, Responsible Consumption and Production, 14, Life Under Water, 10, Reduced Inequalities, and 2, Zero Hunger.

With the collaboration: