ASK A SCIENTIST

Here are the questions we have received so far. If after reading them you are still wondering about something, scroll down to the bottom of the page and send us your question by filling out the form. We will answer you and also post your question here.

Is a tuna fish similar genetically to a mouse?

__________________________

Jonathan, from Israel, asks: Is a tuna fish similar genetically to a mouse?

Natalia Diaz from AZTI answers: All living organisms share some basic genetic similarities due to the universal genetic code, like a language that all living things on Earth use to carry instructions for making essential molecules for life.

Tuna and mice are like distant cousins which share a common ancestor. This common ancestral species, genetically evolved thorough millions

and millions of generations adapting to different environmental conditions.

As a result of this evolution, tuna fish have fins and gills, which help them breathe underwater and swim. Mice, on the other hand, have fur and tiny paws, and they breathe air through their noses, just like we do.

What do tuna eat in the waters around the Balearics?

______________________________

Marc from Mallorca asks: What do tuna eat in the waters around the Balearics?

María Valls Mir, a scientist at Centro Oceanográfico de Baleares, replies.

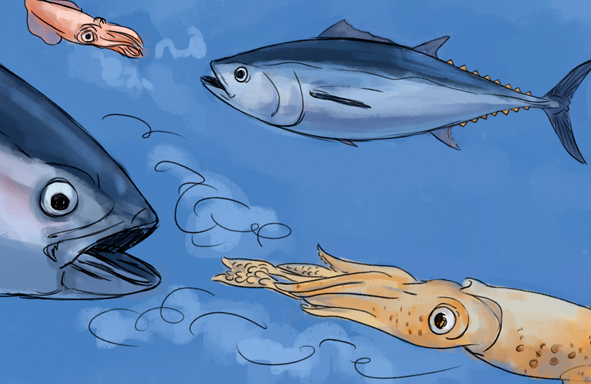

In general, tuna are opportunistic feeders, which means they eat whatever resources are available. Specifically in the Balearics, there have been feeding studies of Atlantic bluefin tuna in their larval stage during the first 25 days of life (less than 15 mm) which have found that they feed on small crustaceans in plankton, copepods and water fleas, and they are also cannibalistic, eating smaller larvae of Atlantic bluefin tuna and other species of tuna.

We know less about juveniles and adults. There have been detailed feeding studies studies of albacore (Thunnus alalunga) during their reproduction in the islands’ waters, when they eat mesopelagic fish such as barracudinas, lantern fish and small crustaceans that form part of plankton. Mesopelagic fish are species that spend the day in deep, dark waters between 200 and 1000 metres, and come up to the surface to feed at night. The

diet of Atlantic bluefin tuna could be similar to that of albacore.

In other regions of the Western Mediterranean, juvenile and adult Atlantic bluefin tuna feed on mesopelagic fish and crustaceans, but also eat cephalopods such as squid and fish such as sardines and anchovies. Some of the most important feeding zones for Atlantic bluefin tuna are found in the Atlantic Ocean in high altitudes, where they feed on very abundant, oily fish such as herring and mackerel.

Do heatwaves affect fishes’ otoliths, causing them to become disoriented, and interfering with the migration process?

________________

Carlos from Valencia asks, “Do heatwaves affect fishes’ otoliths, causing them to become disoriented, and interfering with the migration process?”

Karin Hussy, from the Technical University of Denmark, replies:

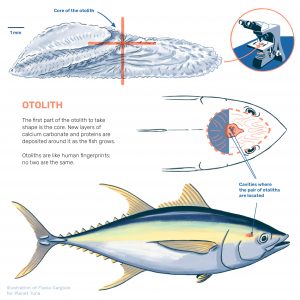

“A heatwave, which generally lasts for a limited period of time, has no effect on the development of otoliths. Movements during heatwaves are the result of physiological stress, which causes fish to require more food and to find colder water.

It’s true that under normal nutritional and temperature conditions, fishes’ otoliths grow at the same speed, but otherwise there would be a disconnection which would cause the otoliths to become larger, in relative terms. In any case, this is a long-term process that is not related to temporary heatwaves.”

What are the best sources of research on the migratory patterns of bigeye and yellowfin tuna? Is there a difference between the migratory patterns of these two species?

__________________________

Mayana, from Brazil, asked us: What are the best sources of research on the migratory patterns of bigeye and yellowfin tuna? Is there a difference between the migratory patterns of these two species?

Iraide Artetxe from AZTI and Hilario Murua from International Seafood Sustainability Foundation answered:

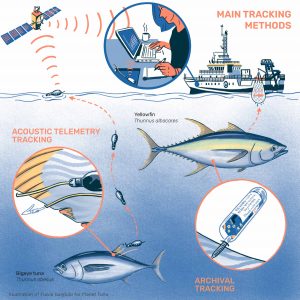

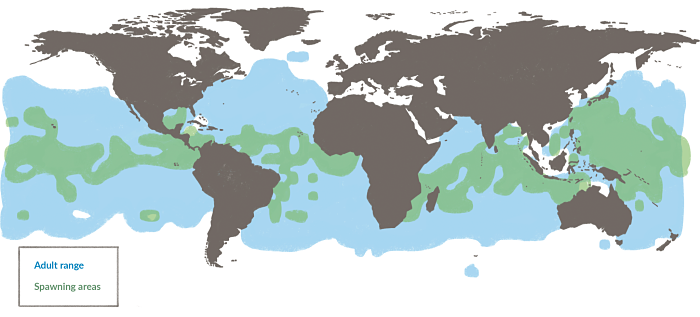

The most common method for researching the migration of tunas, including these two species, involves mark and recapture techniques with artificial tags, which can be classified into two main groups: conventional and electronic tags. Conventional tagging requires marking the fish with an identifier that makes it possible to estimate apparent movement patterns and distances travelled when the specimen is recaptured. Electronic tagging, also known as fish telemetry, does not necessarily require recapture. Besides, it provides more detailed information, such as daily fish position, as well as measurements of the environmental and physiological parameters experienced by the tagged fish. In the specific case of yellowfin and bigeye tunas, conventional and electronic tagging studies show that, broadly speaking, the horizontal migratory patterns of both species are quite similar: large scale movements occur between their spawning habitat (in tropical oceanic waters) and feeding grounds (in more southern and northern oceanic latitudes). These extensive migrations can cover hundreds or thousands of miles. However, there is a difference in the diel vertical migrations of these two species, as bigeye tuna can swim to deeper and colder waters than yellowfin tuna.

Going into further detail, individuals belonging to the same species can show divergent migrations throughout their lives, due to behavioral differences (e.g., “explorers” vs “residents”) among individuals and/or different sub-population dynamics. However, tracking these migratory patterns within the species distribution range is more challenging. Electronic tagging devices can provide geolocation estimates for a given fish, but data over its entire lifespan are not always easy to collect, either because the fish cannot retain the tag over time or because the batteries run out, among other reasons. Alternatively, we can analyze the chemical composition of fish tissues, such as otoliths (i.e. hard calcareous granules found in their inner ear) that can reflect the environment experienced by the fish. As the concentration of certain elements varies in a predictable manner across the ocean and between ocean regions, the element composition found in these fish tissues (e.g. otoliths) can be matched to specific oceanic locations and thus provide a natural geospatial tag. Although this approach shows the potential for deciphering migratory patterns of species with large ocean-basin scale migrations such as yellowfin and bigeye tuna, for the moment it is more of a goal than a reality.

Sources:

McKenzie, J., Parsons, B., Seitz, A., Kopf, R., Mesa, M. y Phelps, Q. (2012). Advances in fish tagging and marking technology. American Fisheries Society.

This content is part of the ocean education program, Centinelas, and deals on Sustainable Development Goal 14, Life Under Water.

With the collaboration:

Do tunas lay eggs with shell?

__________________________

Darl from Philippines asks: Do tunas lay eggs with shell?

Fernando de la Gándara, from the Spanish Institute of Oceanography center in Murcia (Spain), answered: Bluefin tuna, as all pelagic teleosts, expels ovules during laying, which are later fertilized with sperm from two or three males that pursue the female. Therefore, tunas do not lay eggs but ovules, which transform into eggs once they have been fertilized. Both ovules and eggs are small crystalline spheres, close to 1 mm in diameter, surrounded by a thin transparent membrane. No shell is present.

Why is Colombia not well known for tuna fishing, or at least not as much as Ecuador or Peru?

__________________________

Jhon, from Colombia, asked us: Why is Colombia not well known for tuna fishing, or at least not as much as Ecuador or Peru? Are tuna less present off the Pacific coast of Colombia than in Ecuador or Peru?

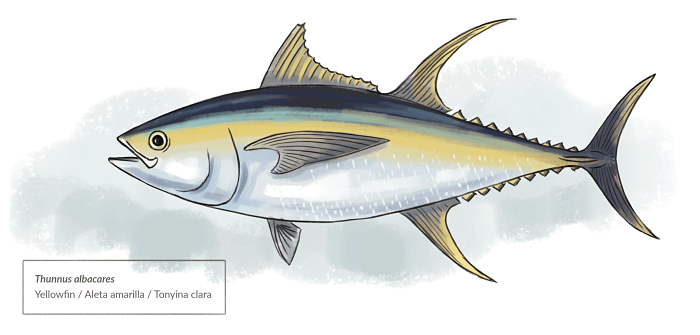

Fernando de la Gándara, from the Spanish Institute of Oceanography center in Murcia (Spain), answered: The abundance of tuna off the coast of Colombia is similar to that of the Ecuadorian coast. It’s surprising that the Pacific port with most tuna landings is Manta, in Ecuador (known as the Tuna Capital of the World), especially yellowfin (Thunnus albacares) and skipjack (Katsuwonus pelamis), with some Pacific bluefin (Thunnus orientalis) as well. Manta is relatively close to Colombia. One of the main reasons why Colombia isn’t especially well-known for tuna fishing is that the Colombian fishing industry (which focuses primarily on its rich sources of freshwater species) is fairly underdeveloped in comparison with Central America and its neighboring countries in South America; Ecuador, Peru, Chile and Argentina are major fishing powers. The market in Colombia is primarily for freshwater rather than saltwater fish, with tilapia as the star species. Surprisingly, the main fish-producing areas in Colombia are landlocked. Some analysts forecast considerable growth in tuna catches for the years ahead, both on the Pacific coast and on the Caribbean, where yellowfin fishing prevails.

What kind of bonito can be found off the coast of Peru?

__________________________

Jhon, from Colombia, asked us a question: What kind of bonito can be found off the coast of Peru, Sarda Sarda or Sarda Chiliensis Chiliensis?

Fernando de la Gándara, from the Spanish Institute of Oceanography center in Murcia, answered: The (sub)species of bonito found off the coast of Peru is Sarda chiliensis chiliensis. Sarda sarda is only found in the Atlantic Ocean, also reaching the Mediterranean and the Black Sea.

How large and deep would have to be a water tank to breed a bluefin tuna? and a yellowfin tuna?

_____________________________________

We have received an anonimous question: how large and deep would have to be a water tank to raise a one month old bluefin tuna? and a yellowfin tuna?

Patricia Reglero from Planet Tuna answered: There are different sizes where you can have one month old bluefin tuna. To have a better view of the installations we are using for our experimental work you can check the webpage of ICAR (Bluefin tuna Research Infraestructure in Murcia, Southeast Spain). The most suitable tanks will be the ones described in that webpage as Facility D) Weaning facility ‐ juvenile tuna weaning unit consisting of a cylindrical tank of 100m3, four of 50 m3 and 4 of 20 m3 with associated recirculation and water treatment system. We are not working with yellowfin tuna since this species is not found in the Mediterranean Sea but they do in Panama and you can see a description of their tanks in their webpage.

How many tuna species are there in Costa Rican waters?

__________________________

Eytan from Costa Rica asked us: How many tuna species are there in Costa Rican waters?

David Die from the University of Miami answered:

Costa Rica has oceans on both sides –on the Pacific and the Caribbean– so it has access to species from both ecosystems. In the Pacific, we find tropical tuna species: bigeye, yellowfin, and skipjack. This area is very productive because of upwelling, which involves masses of deep, nutrient-rich water moving close to the coastline. There’s a great deal of fishing activity from large purse-seine and longline fisheries targeting these species. There have also been reports of Pacific bluefin and Pacific albacore tuna catches in high seas outside Costa Rica’s exclusive economic zone, but they’re small compared to those of tropical tunas.

The three tropical tuna species (bigeye, yellowfin, and skipjack) are also found in the offshore areas of the Caribbean. However, open-water pelagic fish such as tuna are scarce on the Caribbean side. That’s why there’s very little commercial tuna fishing in this area, although there is some sports fishing.

A good source for locating tuna species is the FAO tuna atlas.

Why is it so hard to fish tuna from the shore?

__________________________

Ibon from Bilbao asked us: Why is it so hard to fish tuna from the shore?

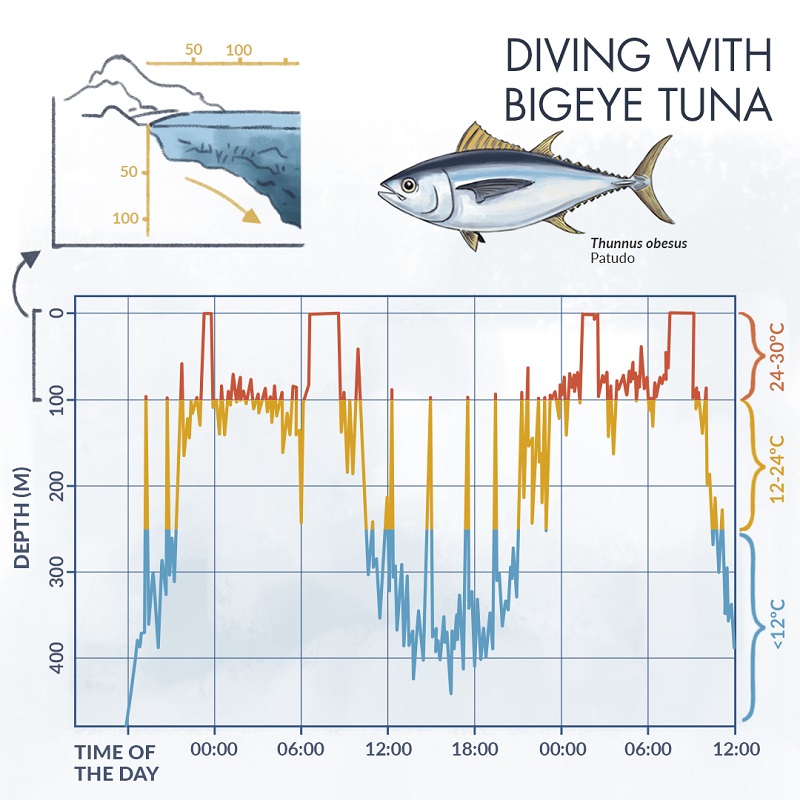

Infographics about bigeye tuna and depths during 24 hours

Patricia, from Planet Tuna, answered: The answer to the question of why it’s so difficult to fish tuna from the shore is related to the question we answered the other day about how deep down they go. As we mentioned, most tuna species live in very deep waters when they’re adults, although they do sometimes come close to the coast. However, some species tend to live in coastal areas, like bullet tuna, whereas others spend more time in open water, like the Atlantic bluefin. Usually tunas come close to the coast searching for food. Besides, they’re more likely to come to the shore in their juvenile stage, sometimes in large groups. These juvenile concentration areas are called nursery grounds. Therefore, if you’re fishing on the shore and you catch a tuna from one of the oceanic species, it’s likely to be a juvenile, whereas if it’s a coastal species such as a bullet tuna, it could also be an adult.

How deep down can tunas swim?

__________________________

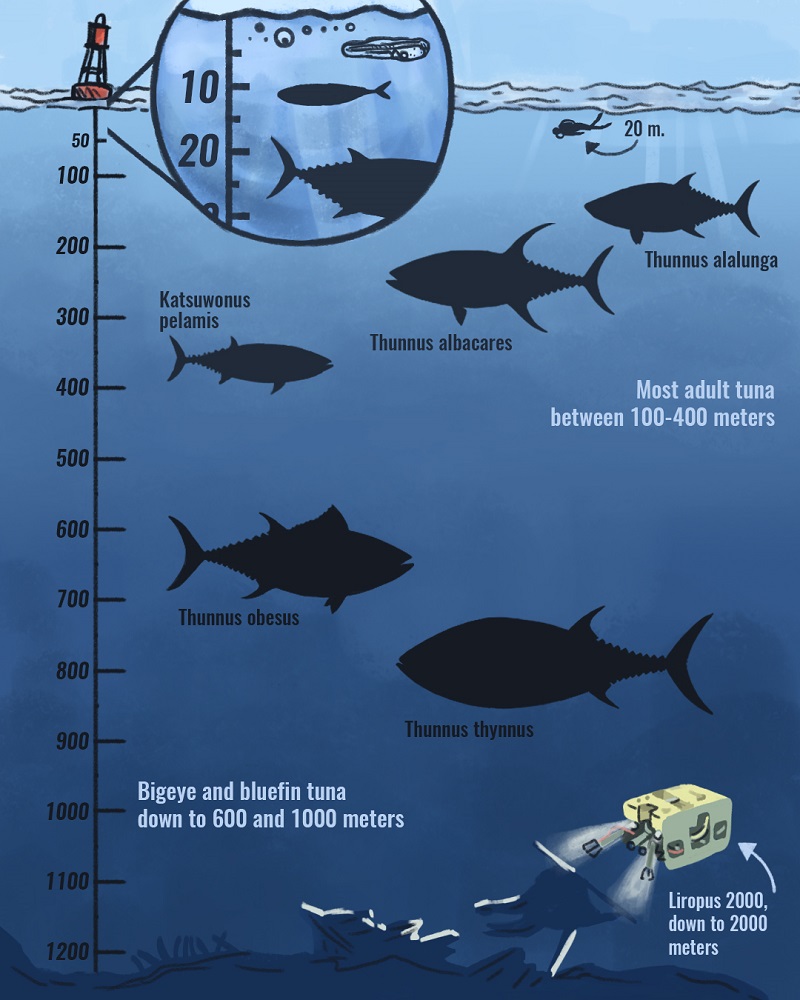

The students from the Lycée Français de Palma asked us: How deep down can a tuna swim? Fermín, from Valladolid, also wanted to know: What is the maximum depth that tunas can reach?

Patricia, from Planet Tuna, and Molly Lutcavage, from Large Pelagic Research Center, answered: The depth at which tunas live or the maximum depth they can reach depends on the species, their physiology, their stage of development, water temperature, light, and the amount of available prey.

To give you a better sense of how this works, try to imagine the sea as a 1,500 m- high column of water that you dive into on a summer day. On the surface, there’s more sunlight, and the temperature is higher than down at the deep end, where the light doesn’t reach and the water is darker and colder. The eggs of all tuna species need warm water, so they stay near the surface. They also float. In addition, the larvae need lots of light to spot their prey among the plankton, and warmer temperatures to survive. So, generally speaking, we could say that during the first month of their lives, all tunas live in the surface water, usually in the top 20-30 meters. Also, in general, when they breed, tunas stay in the surface water so they can spawn their eggs where the environmental conditions are best for their survival.

As they grow, tunas develop muscles and fins for swimming and accelerating quickly. They also develop the ability to raise their body temperature above the surrounding water temperature, which enables them to endure cold waters in addition to warming their eyes and improving their low-light vision. Adult tunas usually live at 100-400 meters below the surface, although the exact depth varies across different individuals and species. In general, tunas spend the daytime in deeper waters than at night. They also often go down into the deepest water in search of prey. Atlantic bluefin and bigeye tunas are the two species that dive deepest, down to 600 and even more than 1,000 meters.

Can one tuna species breed with another from a different geographic location (Atlantic with Pacific or Southern bluefins)?

__________________________

David, from Sweden, asked us: Can one tuna species breed with another from a different geographic location (Atlantic with Pacific or Southern bluefins)?

Fernando de la Gándara from the Spanish Institute of Oceanography answered:

Atlantic (Thunnus thynnus) and Pacific bluefin tuna (Thunnus orientalis) were considered subspecies of the same species until 2003. Although they don’t coexist in the same geographical areas, cross-breeding is certainly a possibility. It may also happen with Southern bluefin tuna (Thunnus maccoyii). In this case, T. orientalis and T. maccoyii do coexist, but hybridization must be very rare, because their spawning grounds don’t overlap.

How can you distinguish a female Atlantic bluefin tuna from a male externally?

__________________________

José Antonio, from Isla Cristina, asked us: How can you distinguish a female Atlantic bluefin tuna from a male externally?

Patricia Reglero and Samar Saber from the Spanish Institute of Oceanography answered:

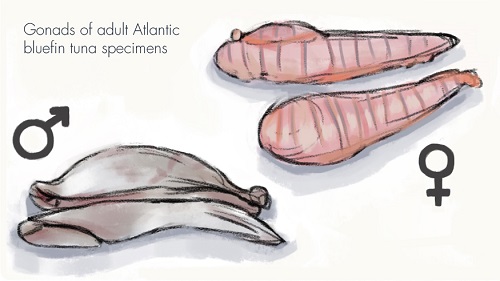

Gonads of adult Atlantic bluefin tuna specimens

A male and a female Atlantic bluefin tuna look exactly the same from the outside. But if we capture a specimen during the spawning season, at night, when the tuna lay their eggs, we can determine its sex by massaging its abdomen and seeing whether sperm or eggs come out. In the Mediterranean, the spawning season runs from June to July.

Are there any records of bigeye tuna (Thunnus Obesus) and albacore (Thunnus Alalunga) in the Gulf of Cádiz, in Spain, and the Algarve, in Portugal?

__________________________

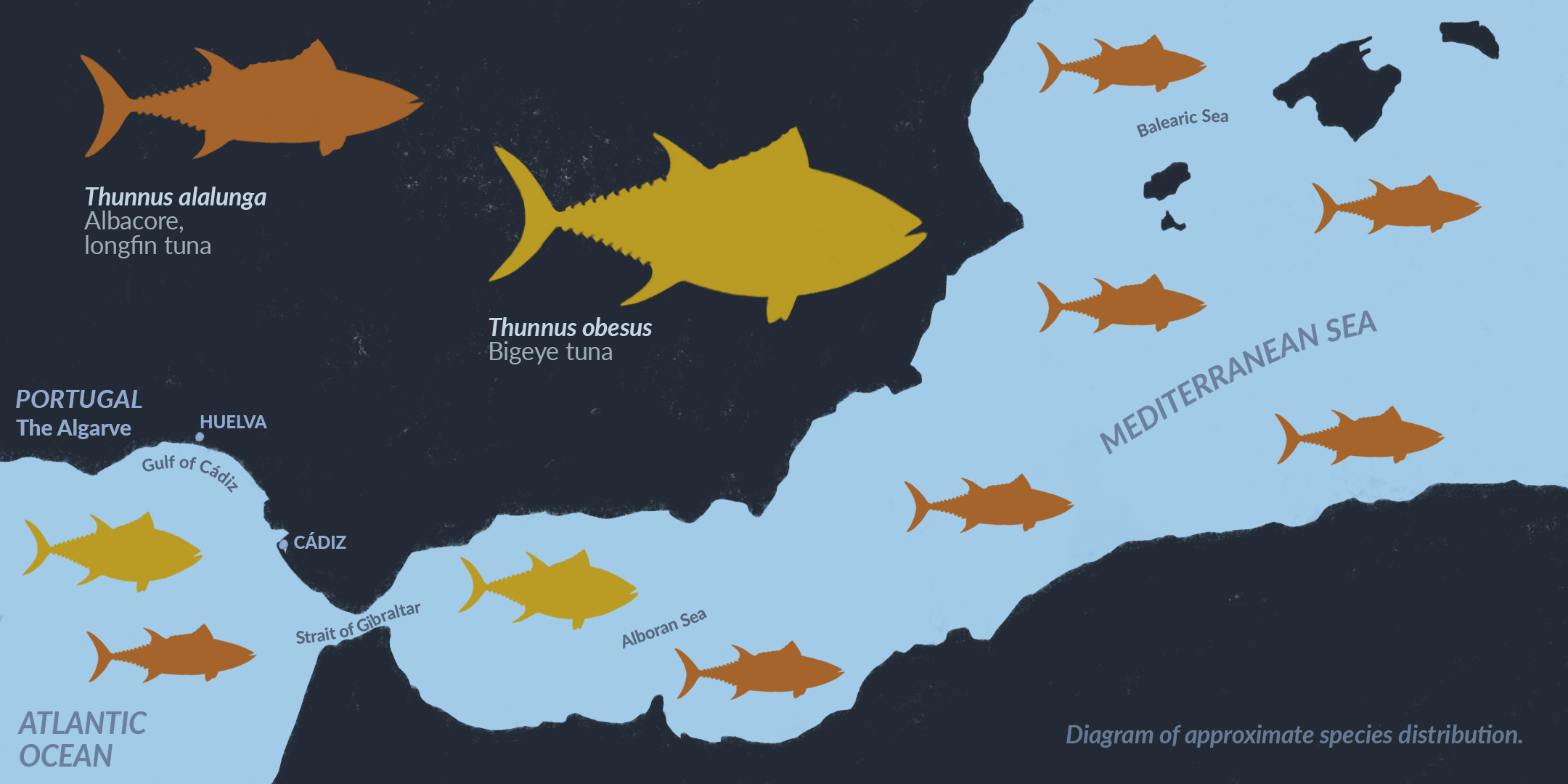

Francisco from Huelva asked us whether there were any records of bigeye tuna (Thunnus Obesus) and albacore (Thunnus Alalunga) in the Gulf of Cádiz, in Spain, and the Algarve, in Portugal.

David Macias and Sámar Saber from the Spanish Institute of Oceanography answered his question:

Diagram of approximate species distribution

Yes, there are records of bigeye and albacore tuna in the area around the Gulf of Cádiz and the Algarve. The Spanish Institute of Oceanography has genetically identified juvenile specimens of both species. When they are young, the two are so similar that it’s easy to get them confused. There have been years when longline fishermen in Huelva occasionally caught bigeye near Cape San Vicente. In these areas, bigeye tuna are at the limit of their distribution and few specimens are found, although in recent years the Cantabrian fleet has reported a rise in catches. In the rest of the Mediterranean and the Cantabrian Sea, albacore tuna are widespread. In the Balearic Islands, one of the main tuna spawning grounds in the Mediterranean, we have never identified bigeye larvae, whereas albacore larvae are fairly common.

Who was the first marine animal?

__________________________

Dylan (five years old), asks: Who was the first marine animal?

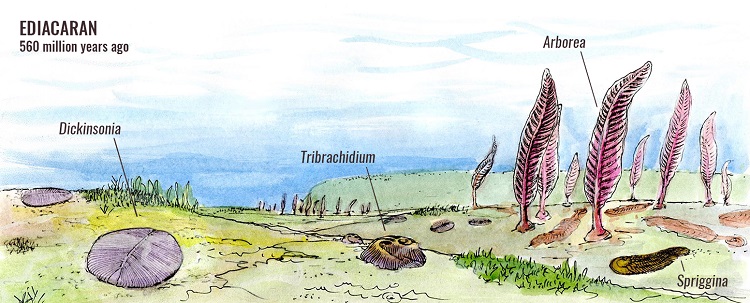

Hannah from Planet Tuna answers: The first marine animals appeared about 560 million years ago, in a geological period called the Ediacaran. As you can see from the picture, these first animals were very odd. Some stayed in one place like a plant and probably filtered nutrients from the water around them. Others could move slowly along the sea bottom. They could afford to be soft-bodied and slow because there were no predators yet. Some of the best-known are Dickinsonia, which looks a bit like a pancake, Arborea, which looks like an upright leaf, and Spriggina, which was one of the ones that could move about.

In the following period, the Cambrian, we see the first predators, as well as many new types of animals with defenses against being eaten such as hard shells, spines, pincers, or the ability to swim away fast. The defenseless Ediacaran animals all disappeared.

The first fish also appeared in the Cambrian. If you want to learn more about these earliest fish, you can watch this video or read this article.

The first marine animals were also the first animals on the entire planet, because life on dry land took a while to evolve, and the first land animals didn’t appear until much later, in the Silurian period.

What is the Smallest Fish?

_____________________

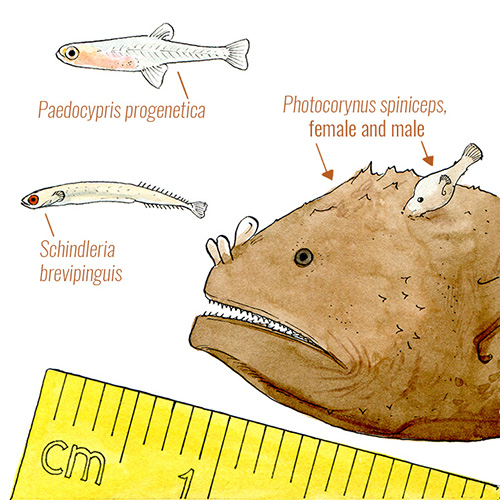

Juan Andrés, age 5, asked us: What is the smallest fish?

Aina and Anna, from Planet Tuna, answered: There’s fierce competition out there for being the smallest fish. According to the Australian Museum, there are three species vying for the World’s Smallest Fish title. One of them is Paedocypris progenetica, a little freshwater species from Sumatra that reaches a maximum length of 10.3 mm. The second contender, Photocorynus spiniceps, doesn’t count because only the male is tiny (6.2mm). He is parasitic on the much larger female (46mm). The third is Schindleria brevipinguis. Australian scientists claim this little fish from the Great Barrier Reef, growing to a maximum length of 10 mm, is the smallest. They base this statement on the fact that it’s not only the shortest, but also the lightest fish of all. That would make Schindleria brevipinguis the winner of the smallest fish category.

What kinds of tunas are there in the Atlantic Ocean?

_____________________________

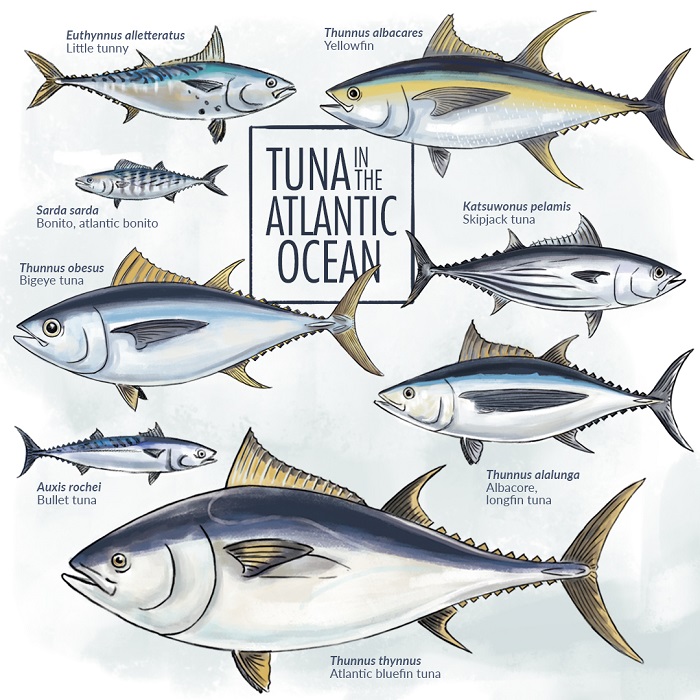

Ibon from Bilbao wanted to know: What kinds of tunas are there in the Atlantic Ocean?

Patricia, from Planet Tuna, answered: The tuna species we find in the Mediterranean are also present in the Atlantic. They are listed here. In addition, among the Atlantic tunas you can also find tropical species that are not present in the Mediterranean, such as yellowfin and bigeye. The International Commission for the Conservation of the Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT), the organization in charge of tuna management in the Atlantic Ocean, has a list of 104 species of tunas, similar fishes, and sharks which you can access on their website, under the Species section. We will be posting information about some of them on Planet Tuna.

What is the life cycle of the yellowfin tuna and its migration routes?

______________________

Claudio, from A Coruña, Spain, sent us the following question: Can you tell me about the life cycle of the yellowfin tuna and its migration routes?

Patricia, from Planet Tuna, answered: It took us longer than we expected to answer this question, because we had to check with the experts and read research papers to realize that there’s still a lot we don’t know about the ecology of this species. For example, some studies show that there’s one single population of yellowfin tuna, which breeds on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean; others suggest the presence of two separate, large yellowfin populations in the Atlantic –one Eastern and one Western. Right now, yellowfins are managed as a single population, which means that much more research has to be done.

Let’s start with what we do know. The yellowfin tuna’s life cycle is one of the best-known among the different tuna species, because the Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission has a laboratory in Achotines (Panama) where experts have been researching its development for years. The life cycle of all tunas is very similar during the egg and larval stages, so you can read our article about the life cycle of the Atlantic bluefin tuna: up until the juvenile stage, both species develop very much the same way. In fact, their eggs are hard to tell apart at first glance, and the only visible difference between the larvae is their pigmentation. The two species differ a lot more in their adult stage. Yellowfins are smaller as adults than Altantic bluefins (although they can be up to two meters long). They start breeding earlier, when they are 2 years old, whereas Atlantic bluefins reach their age of reproduction at 4-6 years. They breed for several months in a row, in tropical waters –in the Gulf of Mexico, the southern Caribbean, off the coast of Senegal, and in the Gulf of Guinea.

As far as the yellowfin’s migration routes are concerned, our colleague Miguel Cabanellas, a scientist at the Spanish Institute of Oceanography, tells us that we know much less about this topic than we do about its life cycle. Little is known about the yellowfin’s migratory patterns. What seems to be sure is that these tunas travel in search of the best areas for feeding –for example, places that are rich in nutrients– or for breeding, which requires, among other things, waters with the right temperature for the eggs and the larvae to survive. The main spawning grounds of the Western population are the Gulf of Mexico (May through July) along with the southern Caribbean (October through March). The same occurs with the areas where the Eastern population spawns: Senegal (April through June) and the Gulf of Guinea (October through March). This last area (the Gulf of Guinea) is not only one of the main spawning grounds, but also a key area for recruitment, which is the moment when, after having reached a certain size or for other reasons, the fish start to be fished for the first time. Juveniles that hatched in this area migrate from north to south along the African coast in search of warmer waters and better food supplies, to then disperse across the entire tropical Atlantic when they reach adulthood. In fact, some studies suggest that the adults migrate across the ocean and that there may be a central area of the Atlantic (30ºW) where adults from both populations gather to reproduce.

Kitchens, L. L. (2017). Origin and Population Connectivity of Yellowfin Tuna (Thunnus albacares) in the Atlantic Ocean (Doctoral dissertation, Texas A&M University).

Margulies, D., Scholey, V. P., Wexler, J. B., & Stein, M. S. (2016). Research on the reproductive biology and early life history of yellowfin tuna Thunnus albacares in Panama. In Advances in tuna aquaculture (pp. 77-114). Academic Press.

Which is the tuna’s natural predator?

____________________

A group of students from the Lycée Français in Mallorca asked us:

Which is the tuna’s natural predator?

Patricia from Planet Tuna answered: When we think of tuna, we usually think of big fish at the top of the food chain. But we have to remember that they hatch from a 1-millimeter egg. So their predators change a lot throughout their life cycle. When they’re only a few days old, during the egg and larva stages, their predators are usually other fish larvae, or even young of their own species, and invertebrates such as jellyfish. As they grow, they can swim faster and get away from smaller predators. At that point, their predators are other fish, but when they reach adulthood, only large predators are able to feed on tuna: other, larger tuna and similar species, large sharks, and killer whales. And, of course, humans.

Do tuna sleep? And if so, how?

________________________

A group of students from the Lycée Français in Mallorca asked us:

Do tuna sleep? And if so, how?

Patricia and Hannah from Planet Tuna answered: First of all we would have to define what we consider sleeping. As humans, we associate sleeping with closing our eyelids, not moving our bodies, and, in many cases, lying down. When it’s dark out, our pineal gland releases melatonin and our body recognizes that it’s time to “shut down the neurons.” If we were to measure the brain’s electrical activity with an EEG when we’re asleep, we would identify a different pattern from the one we would see if we were awake.

Tuna don’t have eyelids, so their eyes are always open. That, in and of itself, doesn’t necessarily mean they’re not asleep: we can’t close our ears, for example, and that doesn’t stop us from sleeping. Tuna can’t ever stop swimming, because they need the oxygen they get from filtering water while they move. If you look into a tank with tuna larvae or juveniles at night, you see they move more slowly, but although we’ve tried, we haven’t yet managed to measure their swimming speed in the dark, nor have we been able to record them without any light. And it appears that the brain activity we associate with sleep in mammals is different from that of fish. There are indications that tuna release melatonin, but we’re not yet sure about the relationship between their daily rhythm and that secretion. So for now all we can say is that, although there’s no scientific evidence of their sleeping, they probably enter some similar state in which they rest and save energy.