Anisakis: how did it get to the fish in my dish?

Find out about Anisakis and avoid food poisoning

______________________

Eating Fish Safely

Do you like fish? Do you want to eat your favorite dishes without worrying about catching anisakiasis? If so, we have good news for you. This digestive disturbance is easy to avoid. Keep on reading and you’ll know how to give it the slip. Meanwhile, you’ll also find out who’s responsible for the problem and how it can make its way to your table uninvited.

Let’s take things one step at a time and start off by explaining what anisakiasis is. As we mentioned, it’s a digestive disturbance caused by eating raw or undercooked fish or cephalopods (squid, octopus, or cuttlefish) which have been parasitized by anisakid larvae. In addition, eating seafood products with Anisakis can trigger an allergic reaction.

How to Avoid Anisakiasis

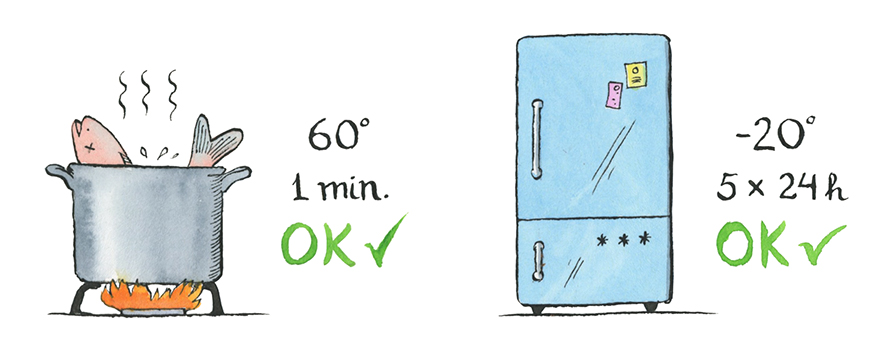

To kill the parasite, we have to cook fish at a temperature higher than 60ºC for at least one minute. If we want to eat raw fish or cook it at a low temperature, like we do with anchovies in vinegar, gravlax, or ceviche, we have to freeze it first. For this precaution to be effective, the fish has be frozen at a temperature no higher than -20ºC for at least five days. The appliance has to be at least a three-star freezer. It’s also important to take into account the volume of fish you’re going to freeze: for example, if you have one kilo of squid, it takes days for the entire mass to reach that temperature. If you buy frozen fish, the problem is solved, because it’s deep-frozen, so it’s safe.

The Stages in the Anisakis’ Life Cycles

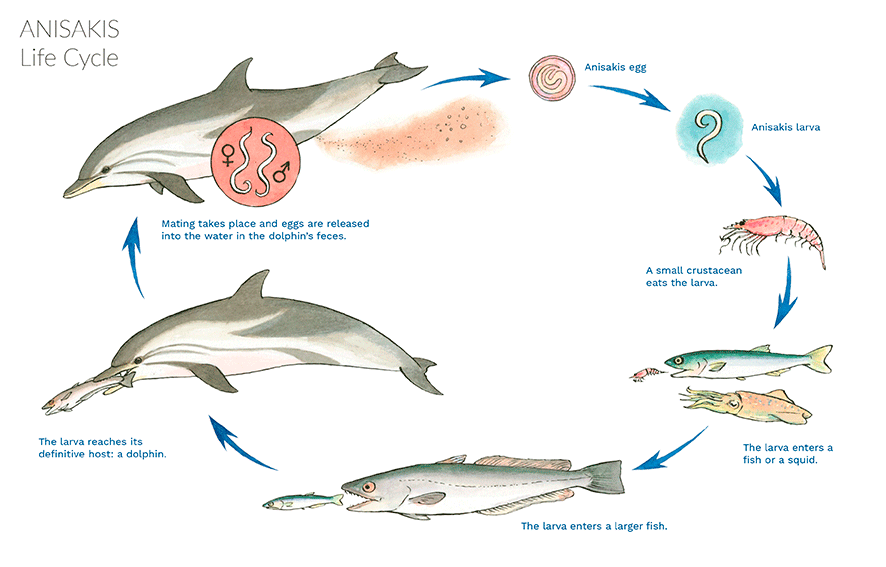

So here’s our next conundrum: what exactly is Anisakis? To answer this question and others, we’re going to get some help from an expert: parasitologist Salvatore Mele. The Anisakis larva is a nematode worm that can grow up to 20 cm long. It’s a parasite with an indirect life cycle, which means that it needs more than one host to complete its cycle. Anisakis breed in the stomachs of marine mammals like dolphins and sperm whales. The eggs are released into the sea with the host’s feces. A larva hatches in each one of these eggs. When it’s in this stage, parasitologists call it L3. The larva is thin, white, and 2 centimeters long. Our little L3 is able to survive several weeks in the water, waiting around for the right animal to eat it. Its aim is to enter a marine mammal again. To achieve its goal, the larva changes homes several times. First of all, it will be on the lunch menu for small crustaceans like krill. These, in turn, will be eaten by fish and cephalopods.

L3 survives the digestive systems of all these organisms. It’s comfortably set up inside a capsule and eats just enough to stay alive. It’s very patient and can remain in this state for years on end. It will only move out of the L3 stage when it reaches a marine mammal –a warm-blooded animal like a dolphin. At that point it will become a pre-adult, known as an L4.

Salvatore Mele points out that the parasite can’t live in just any kind of mammal: each Anisakis species in the world only breeds in the one cetacean species that is its main host. When it reaches the adult stage, the male and female come together inside their marine mammal to breed. The eggs are released into the sea with the host’s feces, beginning the life cycle all over again.

How Anisakis Becomes a Problem for Humans

As we explained earlier, Anisakis could get on with its life without causing us humans any trouble at all, but people who eat fish can catch anisakiasis if their food is infected with this live parasite. Remember that anisakids can spend years waiting for its dolphin to come, but when a human ingests its larvae, something unexpected happens. Humans and dolphins have similar body temperatures, so when they get into our organism, Anisakis larvae think they have finally found their long-awaited dolphin. Salvatore Mele tells us that the Anisakis worm starts living in the person’s stomach or intestine. It irritates the cells in these organs until it creates an ulcer. In most cases, Anisakis ingestion is manifested in a non-invasive way that can pass unnoticed or only cause mild gastrointestinal symptoms. If the body’s defense system doesn’t respond to the attack, any infected mammal risks having more severe lesions on its stomach wall or its intestine. Besides, some people who have been in contact with a live anisakid larva develop an allergic reaction that’s triggered when they come in contact with the worm again, even if it’s no longer alive.

Anisakis’ Favorite Haunts

There’s a list of fish species ranked according to their chances of having Anisakis. Small pelagic fishes like anchovies and chub mackerel are the riskiest, because we often eat them raw. Large pelagic species like the Atlantic bluefin tuna aren’t at the top of the list.

However, Anisakis can get into tuna just as it can enter any other fish. If an anisakid worm is hosted in an Atlantic bluefin tuna, something curious may occur. Atlantic bluefin tuna have the ability to increase their body temperature; when this happens, the parasite may think it has finally found its long-awaited warm-blooded host. If so, it starts changing from L3 to L4 and then it’s doomed –because the tuna doesn’t keep its temperature constant, so the Anisakis ends up dying.

Depending on the host species it finds, the Anisakis worm may prefer to encapsulate in the liver, the intestines, the gonads, or the wall of the abdominal cavity. The preference for one organ or another also depends on the species of Anisakis.

Oceans Without Anisakis, Oceans Without Dolphins

“If Anisakis were ever to disappear, it would most likely mean that dolphins had disappeared, too,” says Salvatore Mele. In fact, ever since these marine mammals have been protected, the presence of Anisakis seems to have risen in the oceans. Parasites are not creatures that elicit a lot of sympathy from us, but their presence is an indication that an ecosystem is doing well.

Life is complicated for an anisakid larva. To reach its destination, it has to go through other animals’ digestive systems and remain in a lethargic state of sorts. “If it succeeds in making it all the way through the food chain until it reaches its definitive host, that means everything’s working properly,” says Salvatore Mele.

So, the question we’re putting out there is this: Are we willing to give up dolphins in order to get rid of Anisakis? “Dolphins are important for maintaining the entire ecosystem, just like tuna and all other species; everything’s part of a balanced whole. Consumers have to understand that everything’s interrelated, and that they have to fight Anisakis once it’s out of the water.”

Is There Such a Thing as Anisakis-Free Fish?

Making sure not to eat wild seafood that’s raw or prepared in ways that don’t kill the parasite is one way of avoiding Anisakis. Freshwater fish are not a problem, because they never carry Anisakis. In theory, farmed fish are also Anisakis-free, because supposedly they don’t eat other fish. However, Salvatore Mele has his doubts about aquaculture being the solution. “Is it sustainable to eat only farmed fish? Honestly, I don’t think so; not with the methods we have today, with only a handful of domesticated species.” As he sees it, fisheries planning makes more sense than setting up fish farms: “What’s better, to ensure that food chains are working properly or to set up a dozen or a thousand fish farms? It think if it’s done right, fishing from the sea is more productive and sustainable.”