We’re researching the calorie intake of bonito larvae

Spend a day in the lab with Planet Tuna Scientists

__________________

The seas and the oceans are the largest unexplored areas on our planet. Many organizations and individual scientists are focusing their efforts on getting to know this fascinating environment.

Puerto de Mazarrón (Murcia) is the site of one of the centers that belong to the Spanish Institute of Oceanography in Murcia, an experimental marine culture plant devoted to researching a variety of marine species in captivity.

We traveled there this past June to learn more about tuna. Research on tuna species is essential for us to ensure sustainability for them and for their environment. Ultimately, our knowledge of tuna allows us to make better decisions for their current and future conservation and preservation.

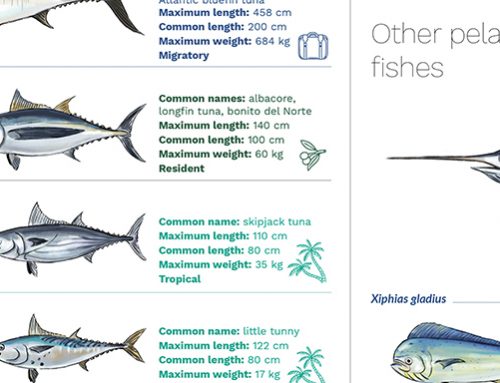

The purpose of our stay in Mazarrón was to measure the metabolic expenditure of tuna larvae (in this case, of the Atlantic bonito, Sarda sarda) –in other words, to know how many calories they use to swim, grow, and stay alive.

Knowing this aspect of their biology will help us estimate the amount of food they need for their survival and how that amount varies according to the temperature and the size of the larva as it grows.

A Team Effort

First of all, where can we get the larvae for our experiment? Collaboration with other professionals is key for scientific work –in this case, with the fishermen from Almadraba la Azohía (Murcia). Atlantic bonito spawn in June along the coast of the Western Mediterranean.

We joined the fishermen to head out to sea and catch breeding-age specimens. On board, we mixed eggs and sperm from female and male bonitos to get fertilized eggs.

To do this, what you do is put the eggs in a bucket of water, add a few drops of sperm, stir, and you’re ready to go!

Here are the gonads of a female, with eggs that are ready to be released into the water, and the gonads of a male, which produce sperm.

From the Sea to the Lab

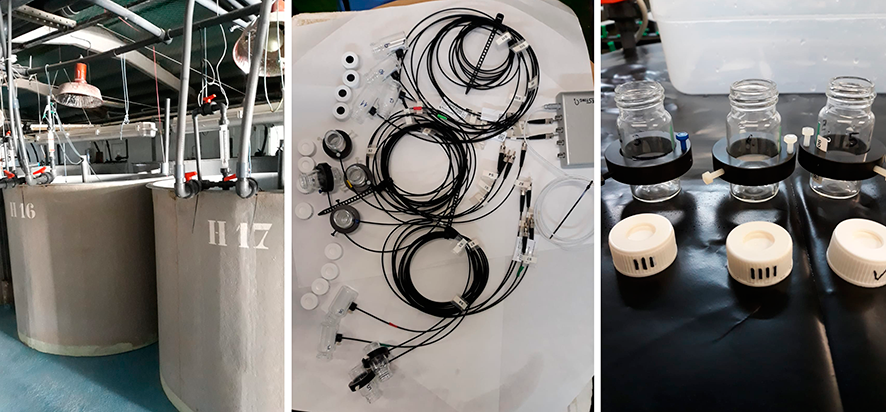

We put the fertilized eggs into 1500-liter tanks, where they turn into larvae and… we’re ready to do our research.

After 48 to 72 hours, the time it takes for a bonito egg to become a larva, we take a few larvae out of the tank to use them for our experiments. We do our research in the dark so the larvae will stay as calm as possible. We work with red light bulbs and place the larvae in individual vials. Using a respirometer that connects the vials to a computer, we measure the drop in oxygen.

When we subtract the oxygen left after 50 minutes from the total at the beginning, we find out how much oxygen each one of the larvae has consumed, and, therefore, its metabolic expenditure.

We’re still in the process of analyzing the results, and it will take us a few weeks to have our first definitive results. We’ll be back in the autumn to tell you about some of them.

You can follow this research on our social media using the hashtag #DesdeMazarrón