Atlantic Bluefin Tuna: The Path to an Amazing Recovery

________________

The Atlantic bluefin tuna recovery plan is an example of successful management. Social pressure led politicians to take drastic protection measures based on scientific evidence –and they worked. When issues are taken seriously and resources as well as political will are set in motion, the right measures can lead to a rapid recovery, even if they’re not the only factors involved in the process.

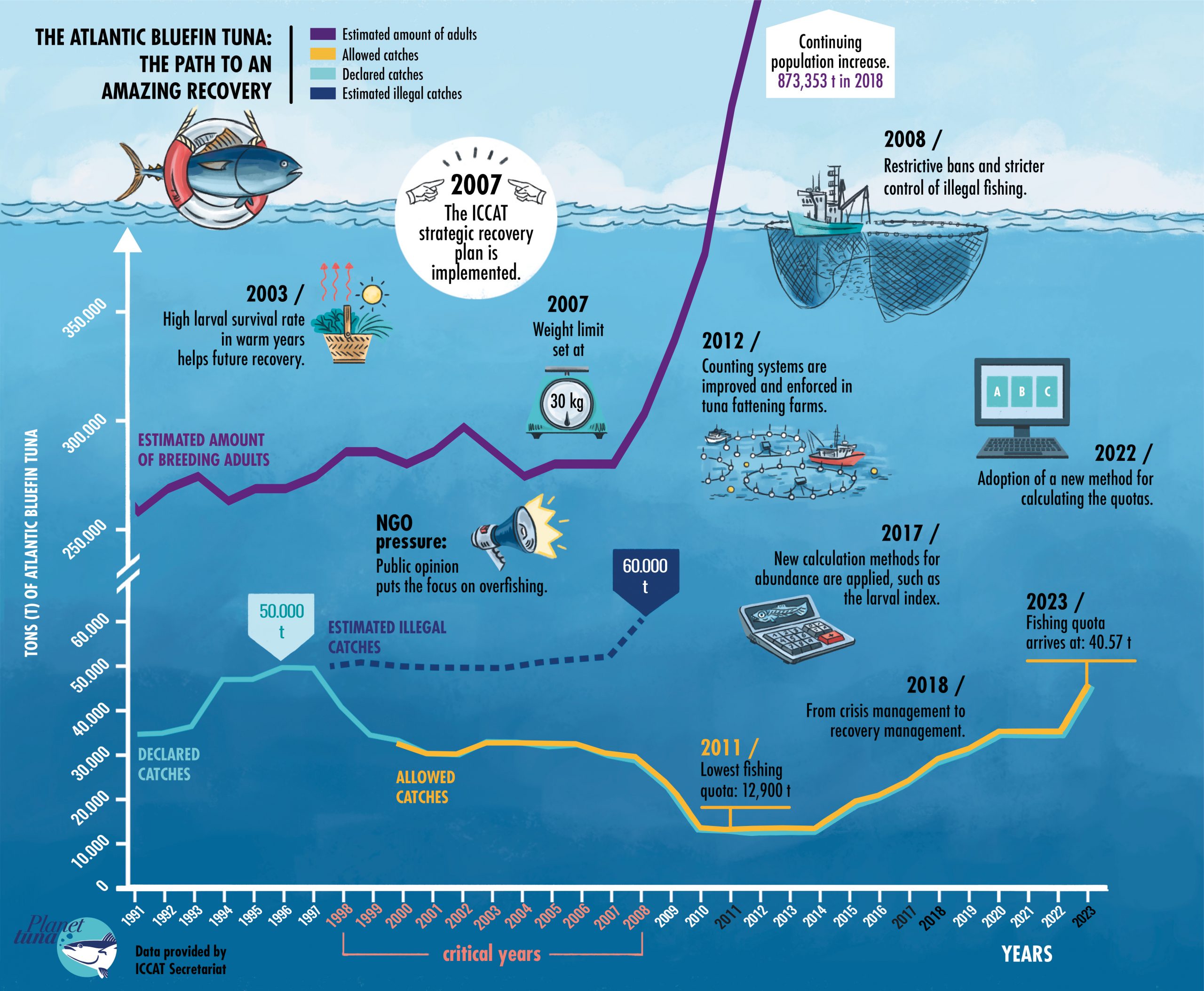

Visual chart //Timeline of the milestones in the recent history of the recovery of the eastern stock of Atlantic bluefin tuna, updated until 2023.

Overview of the Status of the Atlantic Bluefin Tuna

In the mid-1970s, scientists started to see that the breeding population of Atlantic bluefin tuna was declining yearly. A rising market demand had led to a significant increase in catches, reaching 50,000 tons per year in the 1990s. The species was even considered to be on the brink of collapse, and by the end of the 20th century, protective measures were implemented. These included setting catch quotas of around 30,000 tons and a minimum size of 6.4 kg to at least protect individuals under 1 year of age. Unfortunately, it didn’t help much: catches were still above 50,000 tons, partly due to poaching and lack of control over catches. It became apparent that if no urgent action was taken, the species was doomed to extinction, at least as an economically viable resource. The alarms went off, and –maybe because it was an iconic species, so broadly known and with a high commercial value– both the media and governments, driven largely by social pressure and the efforts of several NGOs, paid attention. Finally, in 2007, the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT) established a special recovery plan for the species that has had excellent results.

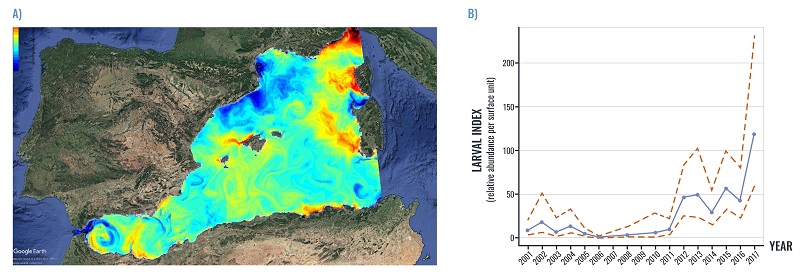

In 2009, Greenpeace and Adena WWF suggested creating a sanctuary around the Balearic Islands (outlined in green).

The main measure involved drastically reducing fishing quotas, to just over 10,000 tons, while also implementing control systems to reduce poaching. Another key measure was to ban fishing for Atlantic bluefin tuna below spawning age, increasing the minimum size to 30 kg. Therefore, many of the tunas that are born in the Mediterranean and leave to feed in more productive areas such as the Bay of Biscay have a much better chance of surviving and returning to the Mediterranean to spawn every year. As far as fishing techniques were concerned, locating schools of tuna from light aircraft was forbidden, and various time and space restrictions were also established for certain fleets, such as large longliners measuring more than 24 m in the East Atlantic and the Mediterranean, or purse seiners in the same area as of July 1st.

“With the ban on juvenile fishing, more than a million fish have been saved every year. The surveillance and control measures used to enforce catch quotas, with official ICCAT observers monitoring the operations, have ensured that, for the most part, the actual catches correspond to the planned quotas,” according to Francisco Alemany, Coordinator of the Grand Bluefin Tuna Year Programme (GBYP), one of the ICCAT’s main scientific programs.

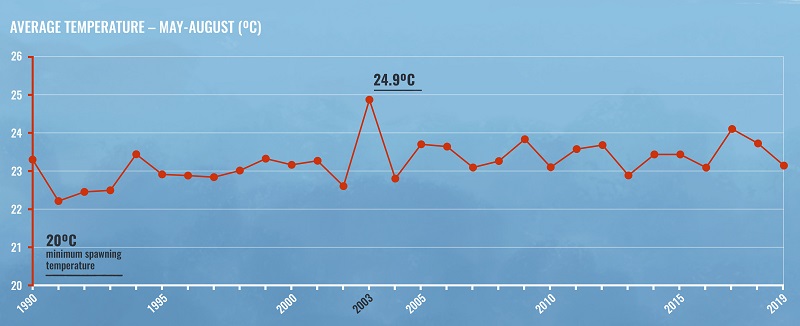

The recovery of the species has been a management success, although the climate has also played an important part. Francisco Alemany points out that we had a series of “very good years in terms of the survival of eggs and larvae, such as 2003, a year with high temperatures during the species’ spawning season in its main breeding grounds. That led to a spectacular recovery of the stock, which nobody expected in such a short time. But we have to be careful, because the environmental conditions can go either way.”

2003 was the warmest year during the Atlantic bluefin’s breeding season, contributing to a higher larval survival rate and speeding the species’ recovery.

The Grand Bluefin Tuna Year Programme (GBYP)

The GBYP also emerged in response to the species’ collapse in the early years of the 21st century. The GBYP was established in 2008, with 80% of its funding provided by the European Union. This scientific program aims to improve the quality of the available data for the species, the knowledge of its biology and ecology, and the mathematical models used to evaluate the population status. “The bluefin is at the forefront of research due to the boost it has received in recent years – and also because it’s an iconic species that has always drawn researchers’ attention,” says Alemany.

One of our aims as scientists is to include environmental variables in our advisory models. For example, temperature (A) determines where we find larvae, enabling us to quantify their abundance (B).

Given that the Atlantic bluefin tuna was doing so well, the possibility of putting an end to the special plan established in 2007 was considered, and it has recently been replaced by a management plan. The main difference between the recovery plan and the management plan is the overall goal. The recovery plan aims not only to meet the minimum requirement for the stock’s sustainability, but also to increase the abundance of spawners in response to a situation considered to be below those limits, while the latter is a standard management plan that ensures sustainability once the minimum stocks are guaranteed.

Scientists and Social Pressure

The recovery of the Atlantic bluefin tuna is an example of success –but we can’t lower our guard. Knowledge-based management, integrating scientific results into the decision-making process, is crucial to address the current challenges for conservation and sustainable use of resources. Unfortunately, in most cases they aren’t taken into account. Social pressure is important for scientific evidence to have an impact on management plans.

This article is included within the dissemination tasks of the European project PAradigm for Novel Dynamic Oceanic Resource Assessments PANDORA.

References for further reading.

-Ingram W y colaboradores (2017) Incorporation of habitat information in the development of indices of larval bluefin tuna (Thunnus thynnus) in the Western Mediterranean sea (2001-2013). Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 140: 203-211

-Porch, C. E., Bonhommeau, S., Diaz, G. A., Arrizabalaga, H., & Melvin, G. (2019). The Journey from Overfishing to Sustainability for Atlantic Bluefin Tuna, Thunnus thynnus. The Future of Bluefin Tunas: Ecology, Fisheries Management, and Conservation, 3.

–http://www.perseus-net.eu/assets/media/PDF/EU_Maritime_Day_May2015/4263.pdf